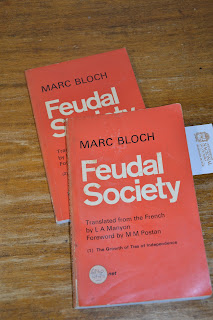

Between dodging viruses and pondering fascism and climate disasters, I have been re-reading a truly uplifting book which I hadn't visited for many years. It's the masterpiece of the French historian Marc Bloch, Feudal Society, first published in 1940. I have a 2-volume paperback of the English translation, which I bought as a student for the terrifying price of 3 dollars and 60 cents.

It's social history or historical sociology, whichever you like. Bloch set himself the austere task of anatomizing a whole society, tracing the basic relationships that made it a distinct social formation. But it is also full-blooded history, concerned with the conditions that brought this society into being, its attitudes, its divisions, its conflicts, its laws; with how it survived in western Europe for five hundred years or so, and how it changed.

Bloch's picture of feudalism isn't derived, as so many discussions of social structures are, from a pre-formed model. It's built up from a wide range of the surviving evidence: handwritten documents of course, but also the names of villages, the shapes of fields, the decorations of churches, and so on. And it's far from static. The book briskly narrates invasions, technological changes, intellectual debates, feuds; and it's concerned not just with mapping divisions in feudal society, but, in some detail, with how new hierarchies were made.

And for all the austerity of the task, Bloch is a lively writer. He has verve and humour. Sometimes he takes the reader aside for a moment, to talk about the fragmented state of the evidence, or to speculate on mediaeval minstrels' sources for the stories they chanted and sang. The feudal period, he notes, was one of the great ages of forgery, with landowners, kings, monastries and even the Popes relying on grossly fabricated documents. Fake news is nothing new!

Some other lines of thought also bring me back to the present.

Bloch suggests there was in those days a pervasive sense of precarity, even of doom.

Especially in the earlier centuries, people widely thought they were living in

the end times, that human history did not have many more years to run. I'm hearing some of those tones now, as we contemplate climate catastrophe and the refusal of state and corporate power-holders to make a real change of direction.

Eighty years after Feudal Society was published, it's easy to see its limits. For one thing, half the population of feudal society is missing: the book says almost nothing about women's lives. (Ironically, the title in French is feminine: La société féodale.) Doubtless, too, the book is quite outdated as historiography. Its division of early and late periods seems mechanical, and later historians have found out much more about the common people than Bloch did. But I still think it was a remarkable piece of work.

I have two other books by Bloch, very different. One was used as a textbook when I was a student at the University of Melbourne, the reflective essay The historian's craft. The other, less known to academics, is Strange Defeat. Bloch was an officer in the French army in both world wars. He briefly escaped at Dunkirk from the German invasion in 1940 but returned to France. Strange Defeat is a memoir of his experience and a reflection on the collapse. As a Jew, Bloch was in the cross-hairs of Vichy and Nazi antisemitism. He joined the resistance and went underground as a courier and organizer; was finally captured by the secret police, tortured and shot. The rest is silence.